Definite iteration

You can use a while loop to go through the items in a list, just like we used while loops to go through strings. The following program prints out the items in the list, each on a separate line:

my_list = [3, 2, 4, 5, 2]

index = 0

while index < len(my_list):

print(my_list[index])

index += 13 2 4 5 2

This obviously works, but it is a rather complicated way of going through a list, as you have to use a helper variable index to remember which item in the list you're at. Fortunately, Python offers a more intuitive way of traversing through lists, strings and other similar structures.

The for loop

When you want to go through some ready collection of items, the Python for loop will do this for you. For instance, the loop can go through all items in a list from first to last.

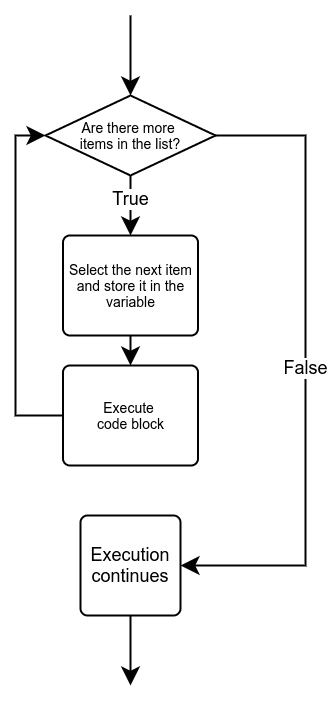

When using a while loop the program doesn't "know" beforehand how many iterations the loop will perform. It will repeat until the condition becomes false, or the loop is otherwise broken out of. That is why it falls under indefinite iteration. With a for loop the number of iterations is determined when the loop is set up, and so it falls under definite iteration.

The idea is that the for loop takes the items in the collection one by one and performs the same actions on each. The programmer does not have to worry about which item is being handled when. The syntax of the for loop is as follows:

for <variable> in <collection>:

<block>The for loop takes an item in the collection, assigns it to the variable, processes the block of code, and moves on to the next item. When all items in the collection have been processed, execution of the program continues from the line after the loop.

The following program prints out all the items in a list using a for loop:

my_list = [3, 2, 4, 5, 2]

for item in my_list:

print(item)3 2 4 5 2

Compared to the example at the beginning of this section, the structure is much easier to understand. A for loop makes straightforward traversal through a collection of items very simple.

The same principle applies to characters in a string:

name = input("Please type in your name: ")

for character in name:

print(character)Please type in your name: Grace G r a c e

The function range

Often you know how many times you want to repeat a certain bit of code. You might, for example, wish to go through all the numbers between 1 and 100. The range function plugged into a for loop will do this for you.

There are a few different ways to call the range function. The simplest way is to give the function just one argument, which signifies the end-point of the range. The end-point itself is excluded, just like with string slices. In other words, the function call range(n) provides a loop with a range from 0 to n-1:

for i in range(5):

print(i)0 1 2 3 4

With two arguments, the function will return a range between the two numbers. The function range(a,b) provides a range starting from a and ending at b-1:

for i in range(3, 7):

print(i)3 4 5 6

Finally, with a third argument you can also specify the size of the step the range takes between each value. The function call range(a, b, c) provides a range starting from a, ending at b-1, and changing by c with every step:

for i in range(1, 9, 2):

print(i)1 3 5 7

A step can also be negative. Then the range will be in reversed orded. Notice the first two arguments are also flipped here:

for i in range(6, 2, -1):

print(i)6 5 4 3

From a range to a list

The function range returns a range object, which in many ways behaves like a list, but isn't actually one. If you try printing out the value the function returns, you will only see a description of a range object:

numbers = range(2, 7)

print(numbers)range(2, 7)

The function list will convert a range into a list. The list will contain all the values that are in the range. The Advanced Course in Programming course, which follows this one, will shed more light on this subject.

numbers = list(range(2, 7))

print(numbers)[2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

A reminder of the demands of the automatic tests

So far, when the exercises have asked you to write functions, the templates have looked like this:

# Write your solution here

# You can test your function by calling it within the following block

if __name__ == "__main__":

sentence = "it was a dark and stormy python"

print(first_word(sentence))

print(second_word(sentence))

print(last_word(sentence))From now on there will be no more reminders in the templates to use the if __name__ == "__main__" block. However, the automatic tests will still demand its use, so you will have to add the block yourself when you test your function within the main function of your program.

NB: some exercises, like the Palindromes exercise coming up in this section, expect you to also write code which calls the function you wrote. This code should not be placed within an if __name__ == "__main__" block. The automatic tests will not execute any code within that block, so your solution will not be complete if you place your function calls there.

In these exercises we will be using lists as arguments and return values. This was covered in the previous section, if you need a refresher.

Finding the best or the worst item in a list

A very common programming task is finding the best or worst item in a list, according to some criteria. A simple solution is using a helper variable to "remember" which of the items processed so far was the most suitable. This temporary best choice is then compared to each item in turn, and at the end of the iteration the variable contains the best of the bunch.

A rough draft which doesn't quite compile yet:

best = initial_value # The initial value depends on the situation

for item in my_list:

if item is better than best:

best = item

# We now have the best one figured out!The details of the final program code depend on the type of the items in the list, and also on the criteria for choosing the best (or worst) item. Sometimes you may need more than one helper variable.

Let's practice this method a little.

You can check your current points from the blue blob in the bottom-right corner of the page.